As a child in the 1930s, Max Baldwin was taunted by other kids as “a cripple”, having survived polio as a baby, which left him with leg paralysis. Little did they know Max was made of sterner stuff.

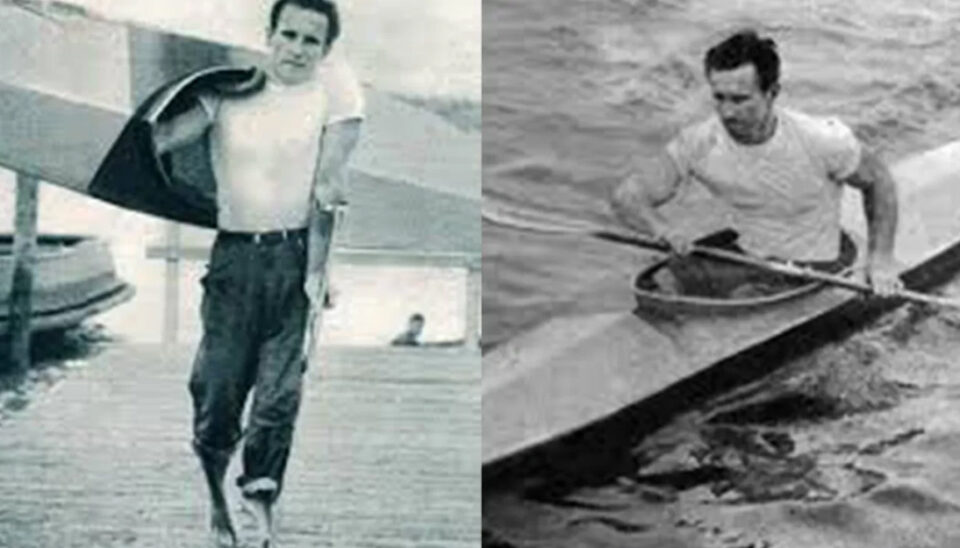

Twenty years later, he became an Olympian, selected to compete for Australia in the 10,000m kayak marathon at the Melbourne 1956 Olympic Games.

Max’s 96-year journey through life has been characterised by a rare determination and resilience, his buoyant nature the antidote to all the trials that life could throw at him.

Struck by polio when he was just six months old, he was still unable to walk at three, when he was sent from his family home near Ballina to Sydney for three months’ treatment at the Sydney Children’s Hospital, where they put his legs in metal callipers.

That made little difference, but a follow-up appointment with Sister Elizabeth Kenny, who pioneered a new approach to polio treatment which involved mobilising the limbs, changed his life.

She advised that it was too late to treat him with her methods, but suggested to his parents that they remove the callipers on his legs and have wooden crutches made to help him to move around. She provided a hand-drawn sketch, which his father Ernie used to make the crutches.

“They were my saviour, as far as mobility was concerned.”

Young Max learned to use them at home, but it was only when a school bus service was established between Lismore and Ballina when he was seven years old, that he had the opportunity to go to school.

“We lived about a mile from the road, so my mum would carry me to the bus in the morning and they would pick me up and drop me at school in East Ballina, and in the evening the bus would pick me up and drop me off, but then I would have to struggle and hope to do the mile home on my own,’’ he recalled.

Occasionally, a passing drover would give him a lift on his horse, but mostly, he had to complete the journey unaided.

There was no thought that he would be able to play sport. “When I went to school, I was never put in a competition, I was always a scorer or checking the kids coming over the line. There was nothing for disabled people and you were harassed at school. Kids would push you over and that sort of thing.’’

During the second World War, his parents moved the family to Redfern in Sydney. His elder brother Geoffrey enlisted and was killed in Papua New Guinea.

His younger brother Beres and sister Gwenda went to an acrobatics school, Sparkes’ Tumbling Academy in Newtown, and developed an act that they performed in variety shows at the Tivoli Theatre and other venues.

“One day when I was about 17, I went to watch them train, and there was a bloke there doing some hand balancing, and I thought ‘I could do that’.”

The legacy of his many years using crutches was exceptional upper-body strength and he quickly mastered hand-balancing, before joining the YMCA gymnastics club, where he expanded his gymnastic range. A year later, he won state titles on the rings and floor exercise.

“That opened a lot of doors for me,’’ he recalled.

One of his fellow gymnasts was also a member of the Youth Hostels Association and invited him on a weekend away at a hostel at Kyandra, near Cooma, late in the snow season.

He had never seen snow before but gamely attempted to ski, using one ski and his two sticks, falling regularly until a French skier approached and informed him that French war veterans who had lost a leg were skiing with modified crutches that had small skis on the ends. His new friends at the YHA pitched in to make some for him and his skiing improved remarkably. He became a pioneer of three-track skiing in Australia.

The following season he entered a downhill race and won a trophy, and then met his future wife Morea, also a keen skier. The YHA provided other sporting opportunities and Max jumped into them wholeheartedly.

“I found out there was a canoe club in the YHA and I got involved in that and that opened the door to the Olympics,’’ Max said.

After developing his kayak technique he entered the state titles and won both the 1000m and 10,000m races, which encouraged him to continue.

He entered an annual 100-mile race from Penrith to Hawkesbury River Bridge in a K2 with a friend, and they finished second, after paddling for 14 and a half hours.

The next year he intended only to go and watch the start of the race, but on arrival he felt the urge to compete and asked if he could enter as a single competitor.

“All I had with me was a bottle of water, a few nuts and a couple of biscuits,’’ he remembered.

That year the water was running low in the river system, so there were parts of the course near Richmond where he had to get out of his canoe and drag it across rapids in the dead of night.

“It took me 19 hours but I ended up winning that race, so that was quite an achievement,’’ he said.

He was out training early in 1956, when an acquaintance asked him if he had thought about going to the Olympics, which would be in Melbourne later that year. He hadn’t, but after winning an Australian title that year, he gave it serious thought.

He began training with a coach, Dr Frank Whitebrook, who would go on to become president of the Australian Canoe Federation in the 1960s.

Max paddled on the Cooks River in the morning, before working as a taxi driver from 2pm to midnight to support his wife and baby.

“People don’t understand what sacrifices you make,’’ he said. “The amount of sacrifices athletes had to go through, and still go though, to make it, and the chances are you are not going to make it.’’

In his spare time he combined with a friend to do a hand-balancing act in variety shows. That almost cost him his shot at the Olympics. In the days of strict amateurism, he was required to obtain a certificate from the NSW Gymnastics Association declaring that he was not a professional athlete.

He went to the Olympic trials in Ballarat, where Whitebrook advised him the night before his K1 1000m race that he should not drink any water until after he competed.

He followed that advice but, with only one Olympic place available in each event, it nearly led to disaster. A dehydrated Max finished a close second behind Dennis Green. His saving grace was that Green had already decided to prioritise the K2 10,000m marathon event with his friend Wal Brown, leaving the way open for Max to be selected.

However, the selection committee made an unexpected decision, choosing him for the K1 10,000m marathon instead. Max still feels aggrieved by that decision to this day.

“I had trained for the 1000m, but they came out and said, you’ve made the Olympics, in the 10,000m,’’ he said.

Max did not think he was suited to the longer event, and with only two weeks between the trials and the Games, he did not have time to adjust his training, but he was determined to make the best of the situation.

The canoe team trained on Lake Wendouree in Ballarat in the lead-up to the Games, living in caravans, before moving into army barracks for the Games.

As the day of the Opening Ceremony approached, an official began organising for the rowers and canoeists to go to Melbourne to march.

He said to Max: “What about you Max?”. I said: “What about me?”

He said: “You won’t be marching”. I said: “What do you mean?” He said. “Well, you can’t do it with crutches.”

Max’s reply was succinct: “Listen mate, I am marching,” and he did.

“They let me march. I hobbled around with all the other mob. It was quite exciting, walking around there. You feel like a gladiator, I suppose.’’

“I’ve always said this. Competing in the Games is nothing, the thing is making the Games. You work your butt off and come the day of the trials, you can get pipped by a point and you don’t make it. Once you are in the Team you can relax and do your best. But to get in the Team is the hardest thing. I’ve met quite a few ex-athletes who have missed out by a whisker.’’

“I never ever thought in my wildest dreams that I would be an Olympian, but I remember when I was about 18, the first Olympics after the war (1948), there was an Australian high jumper who won a gold medal (John Winter). I remember talking with my friends and we were saying it would be good to be an Olympian. In those early years it was a pipe dream. But what I say to people is, doors open and you walk past them or you walk through them. Opportunities arrive and that’s how it was with me.’’

He did not stay for the Closing Ceremony of the Games due to the financial pressures he was facing after losing a month’s income, but he did manage to watch the men’s 10,000m at the MCG won by the Vladimir Kuts, before heading back to Ballarat for his competition.

He finished 9th in the K1 10,000m, but still wishes he had the chance to test himself in the 1000m race.

But what I say to my friends is, the thing is not to win, but to compete,’’ he said.

After the Olympics, Max gave up canoeing.

“I went in one or two races, but I’d made so many sacrifices and my good wife had had to put up with so much – I had a little girl at the time and we were living in one room with my mother-in-law in Randwick and we wanted our own place, so I need to work.’’

He trained as a cobbler, while working as a gymnastics instructor at the YMCA. He was then appointed as Physical Director at the YMCA.

After ten years there, he joined the Police Boys Club in Woolloomooloo to run the gymnastics program, where he also took up squash, using an effective ‘rope-a-dope’ strategy to disarm his opponents.

“I started playing for the club in one of the lower grades and I used to compete against the able-bodied fellas and when I walked onto the court, they would think, who’s this old bloke with crutches. I would suck them in. In the warm up I wouldn’t do anything right but when the game started, then I would lift. Before long, they are walking out of the court furious. This old bloke on the crutches has beaten me. I must have won more than 50 percent of my games that way.’’

“You should never under-estimate people in anything.’’

As the first disabled Australian to compete at the Olympic Games, Max has a unique place in our sporting history, which was recognised when he was awarded the Order of Australia Medal.

He was also selected as a torchbearer for the 2000 Olympics torch relay, and carried the flame at Dee Why in Sydney on the morning of the Opening Ceremony.

“It was thrilling,’’ he said.

He said sport became his avenue into society at a time when disabled people were often excluded.

“I have had a wonderful sporting life,’’ he said. “It gave me independence and allowed me to compete against able-bodied people. Life was boring for me until I started gymnastics.”

The rest is history in a truly remarkable life.